What Causes Fussiness and Crying in Infants, and What Helps?

I often talk to lactation clients about what happened during the birth and immediately postpartum, how their infant sleeps, and their concerns about infant fussiness or gas (if they have them), because I find these things to often be connected to infant feeding. Because of my background in anthropology, lactation, and infant development, I am in a unique position to address how these things come together. I will get to the anthropology further on, but first, I’m going to address what the non-anthropological research tell us about things we think might cause crying, as well as excessive, inconsolable infant fussiness and crying, otherwise referred to as colic. Your baby might not have colic, but looking at colic gives us a window into all types of fussiness and crying because both regular crying and the more intense colic crying tend to peak during the so-called “witching hours” and may have similar causes.

Could your baby be allergic to something you eat that is in your breast milk?

It isn’t that common for an infant to develop an allergy to something their mother has eaten. Only about 5% of breastfeeding infants have cow milk protein allergy, the most common one. Infant food allergies are more common in infants whose relatives have a history of allergies, and who are given formula in the first few days postpartum when the gut is more permeable.

Foods in the lactating mother’s diet that infants might react to are milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, and wheat. Cow milk proteins are the most common culprit, but infants who react to dairy often react to soy as well. Newborns with a food allergy can have mucus or blood in their stool and a persistent diaper rash that doesn’t go away until the infant is no longer exposed to the allergen. They might also have other common signs of allergy, such as eczema or a runny nose, and be extra fussy. A baby doesn’t have to have all of these signs present, and sometimes the blood in the stool isn’t visible to the naked eye. Your pediatrician can test a stool sample for microscopic blood. However, blood in the infant’s stool can have causes other than allergy, such as antibiotic use, oversupply, anal fissures, or a viral or gastrointestinal infection.

It’s possible that it isn’t a type of food a baby is sensitive to, but medication or supplements the lactating parent is taking. Caffeine consumption can also make infants irritable, although only a small amount of the coffee or tea you drink gets into your milk and a couple of cups a day normally doesn’t cause issues. Ask yourself if there is any food or substance you ingested shortly before the symptoms began.

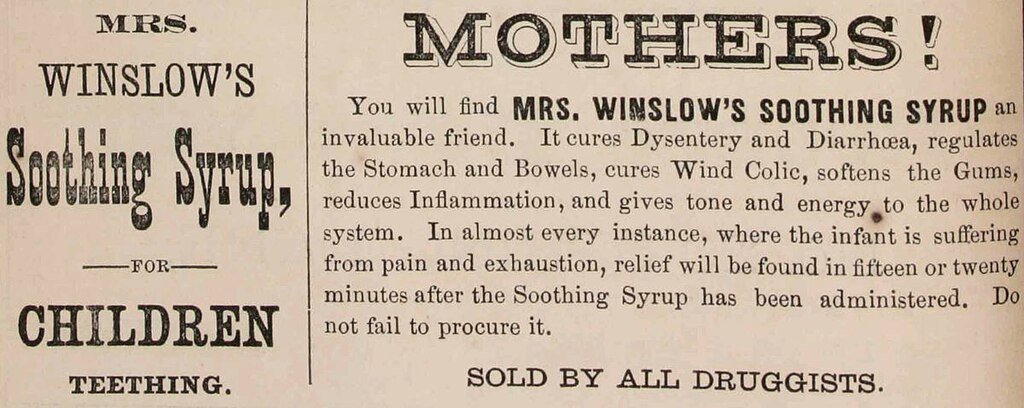

Babies who who were teething or had colic were once given Mrs. Winslowʻs Soothing Syrup. It was created in 1849 by a physician. The magic ingredient? Morphine. Sometimes it quieted babies for good when desperate parents gave them too much. Drooling can start as early as 3 months for non teething reasons, but the first teeth usually erupt between 5-7 months.

According to the Ebers papyrus, ancient Egyptians also gave crying babies narcotics. In this case, opium and “fly dirt which is on the wall” mixed together. Thatʻs fly poop, which contains bacteria and pathogens. The text recommends giving it to the baby for four days but states that it acts at once! The Egyptians were farmers, and we see greater amounts of infant crying in contemporary societies that were hunter-gatherers but recently transitioned to farming, than in contemporary hunter-gatherer societies.

This Egyptian breastfeeding image is from the British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Is the issue reflux?

Most infants spit up. That’s because in early infancy the sphincter that separates the stomach and esophagus is not as effective at keeping milk from coming back up. In some cases, stomach acid in the reflux causes damage to the esophagus, along with pain. Because of this, many parents think that fussiness in their babies might be do to reflux. Most babies are, however, what we call happy spitters. They don’t seem bothered by it, and it is mostly a laundry problem. Reflux ends up being overdiagnosed in infants because the tests for determining if an infant has damage to their esophagus from reflux isn’t that reliable, and doctors often feel pressured by worried parents to prescribe medication. The proton pump inhibitors that are often prescribe have been found to be ineffective in infants. Thickeners can work in formula, but the enzymes in breast milk dissolve the thickeners.

Many breastfed infants who spit up a lot have a mother with an oversupply of milk. The baby gets a lot of milk quickly and is done nursing sooner than expected. Some mothers are anxious that the baby isn’t getting enough milk and try to keep them nursing for longer, resulting in an overfed baby who is more likely to spit up the excess milk.

A review of studies found that in all but one study, it was determined that reflux is not responsible for colic.

Bakers weighing their baby, an advertisement for "Boulangère" chicory. Chromolithograph by L. Olivié, ca. 1890.

Is the baby getting enough to eat? It is certainly possible that a fussy baby is hungry, however, not all crying, rooting, and sucking means a baby is hungry. Babies like to suck for comfort, and because it helps them go to sleep. When they suck their body releases a hormone that makes them sleepy. Babies also cry when put down because they want to be held.

Could the issue be some other type of feeding issue?

Some people speculate that because your milk supply is lower around the late afternoon or evening, that infants cry more at this time because they are hungry. This is not likely the reason because the time period during which your supply is lowest your milk also has more fat in it, which should keep your baby full for longer. Infants who arenʻt getting enough milk are often fussy, however, unless they are severely malnourished, in which case they become lethargic and stop crying to conserve energy. Not getting enough milk can be due to a low supply, a feeding issue, or not feeding the baby frequently enough.

If you have an oversupply your milk will come out faster, and this causes some babies to have intestinal cramping from lactose overload. This can happen with bottles fed too quickly as well. Lactose overload isnʻt the same thing as a lactose intolerance. It is caused by the baby getting so much milk so quickly that the lactase enzyme in the gut that breaks down the lactose canʻt keep up. These infants might have blood in the stool (sometimes it is microscopic) and usually have green stools that can also be mucusy or frothy. Not all green stools mean your baby has this issue though; your baby will temporarily have a green stool when your milk comes in, and green stools can also be caused by something you ate. Mucus and blood in the stool can also be signs of a food allergy.

Some babies are fussy when you try to nurse them because they have a preference for bottles, are reacting to the fast flow of an oversupply, or are being overfed.

There are lots of products marketed to help ease gas pains in infants, none of which has been proven effective.

Woodwardʻs Gripe Water was introduced in 1851 mainly to help with infant gas pains. Early gripe water recipes contained alcohol, sugar, sodium bicarbonate, and herbs. Today, gripe water sold in the U.S. doesnʻt contain alcohol since we now know that can cause developmental problems. Some still contain sugar, which is questionable. Sodium bicarbonate is an antacid, but most fussiness isnʻt attributed to stomach acid.

Is it gas?

Most people assume that colic is caused by gas, but researchers have not been able to determine that it is. Checking for the presence of hydrogen in the breath has been one way researchers have tried to figure out if infants are experiencing excessive gas. One older study that looked at this found elevated hydrogen in most of the colicky babies it studied, but also found elevated hydrogen in infants who were not colicky. This finding has been repeated. Another study on colicky infants showed that they had a normal amount of gas production prior to a crying episode, but had increased gas production directly after the crying episode, leading the researcher to believe that air swallowed while crying itself was responsible for the increase in gas found. This means that the crying was likely due to something other than gas from swallowed air.

Another reason to believe that excessive swallowing of air is not likely a cause of colic, is because Simethicone, a medication that targets the gas in your stomach (which is from swallowed air), doesn't work any better than a placebo at reducing colic. Increased production of gas in the intestines, rather than swallowed air, is what is responsible for most flatulence in adults. We don't know if this applies to infants, but if it does, it means excessive air swallowing could lead to burps and abdominal bloating, but not necessarily flatulence in infants. Flatulence from fermented bacteria in the intestines is related to what you eat and results in smelly farting at night. Needing to burp but not being able to, leads to a feeling of pressure, and perhaps mild discomfort, which in my opinion is less likely to cause pain and crying than intestinal cramping.

Many parents believe their infants are fussy because they have gas, based on the observation that they release gas after they move them around or after the baby arches and lifts the legs. This doesn’t necessarily offer proof that gas is the cause of fussiness, because movement itself is likely to cause infants to belch or fart.

Is the problem related to gut bacteria?

Several studies have determined that infants with colic have a different gut microbiome, with less of the good bacteria and more problematic bacteria than other babies. Because of this, infant probiotics have been marketed as a way to help infants with colic. Our understanding of the microbiome is limited, because it involves complex interactions. However, it is known that infants are “seeded” with good bacteria during vaginal births, and this bacteria sets their guts up to be colonized by the bacteria and oligosaccharides found in breast milk. Infants born via c-section, infants who do not get breast milk, or infants who have had some formula, have different gut microbiota.

Is it hormones?

There is some evidence that increased levels of the hormones motilin and ghrelin, which increase stomach emptying and intestinal muscle contractions, are higher in infants with colic. Serotonin has also been found to be higher in infants with colic, and this hormone also increases intestinal smooth muscle contractions. Infants don't produce their own melatonin until they are about 3 months old , and melatonin relaxes intestinal smooth muscles. This has been put forward as a cause of colic since colic is known to occur during the "witching hours" in the evening, when serotonin levels peak and melatonin would normally be released and able to counter the effects of serotonin. Also, colic tends to disappear around three months of age which coincides with the time that infants start to produce their own melatonin. It nicely address the peculiarities of colic’s timing.

Melatonin is released in the lactating parent in the evening and is transferred to the infant through breast milk. Melatonin has not been detected in formula. However, both breastfed and formula fed infants can have colic. There is a possibility that melatonin amounts are low in infants who are fed pumped milk at night that wasn’t pumped during melatonin production, or in those whose lactating parents are deficient in melatonin. Most of us are not exposed to sunlight all day, and use artificial lighting at night, which can impact our circadian rhythms. However, exclusively formula fed infants don’t receive any melatonin until their bodies produce it on their own around 3 months, yet not all exclusively formula fed infants have colic.

Could colic be related to parenting beliefs, stress, or practices?

An interesting study in 2007 found that infants who were hospitalized because their parents reported excessive crying, were not found to have excessive crying by hospital personnel. It was determined that the parents perceived normal infant crying as excessive and problematic.

Dr. Terry Brazelton tried to figure out how much a normal infant cries and reported that normal "infants cried and fussed for a median of 1.75 hours per day at 2 weeks of age, which increased to a peak of 2.75 hours per day at 6 weeks and gradually declined to less than 1 hour per day by the 12th week of life." Colic would involve more crying than this (three hours or more a day more than three days a week for more than three weeks according to the standard definition), and is also reported to be a more urgent, distressing, high pitched cry. It peaks during the “witching hours” of 3:00 pm to 11:00 pm.

The infants in the 2007 study were far more likely to have had feeding problems and complications during pregnancy or birth. Could it be that a parent with high stress or who wasn’t prepared for the intensiveness of infant care could be less tolerant of infant crying and perceive it to be worse than it is? Is colic then, a problem of inadequate support for parents?

This advertisement from 1913 is for a beer that was marketed to both moms and their babies. It was advertised as “recommended by your physician.” Many doctors at that time believed that it was okay to give alcohol directly to infants (and it was in gripe water), which we now understand to be harmful.

It is possible that some excessive crying is caused by beliefs that infants shouldn’t be or don’t need to be held a lot. One study showed colic to be higher in parents who were worried that their infant would be spoiled, or too dependent on them if they held them all the time and therefore held them less often. Crying rates decreased from 3.2 to 1.1 hours a day in 65 to 70% of purported colicky infants in a different study where parents were instructed to check and see if the infant was hungry, sleepy, wanted to be held, wanted to suck, needed stimulation, or needed a diaper change. Crying was not reduced in infants assumed to be overstimulated and/or ignored. This study was repeated two more times with the same results. Another study, however, found that parenting style makes a difference with general crying, but when it comes to colic, which is thought of as not just as excessive crying but unsoothable crying, parenting style doesn’t seem to make a difference.

There are studies that point to increased depression or anxiety in parents of infants with colic. It makes sense that a depressed mom might not be as responsive to her infant, however, it’s a which came first issue. A baby with colic causes a lot of parental distress and sleep deprivation, and this could lead to or exacerbate existing depression and anxiety.

My own experience with clients has been that most first time parents don’t realize how much newborns want and need physical contact, rhythmic movement, and stimulation. They expect to be able to put newborns down drowsy but awake without them fussing, or put them down right after they have fallen asleep without them waking. When this doesn’t work for most young babies, the parents often believe the crying is related to hunger and represents a feeding problem rather than they need to be held or that the baby needs help going to sleep with movement or sucking. A good deal of the information on infant sleep that parents recieve is not based in science. Of course, sometimes crying is from hunger.

Babies require a lot of holding!

Wearing your baby will keep them calmer, help them nap better, and will keep your arms free so you can carry on doing your daily activities.

What can anthropology tell us?

Anthropology can shed light on all of this., because hunter-gatherer babies don’t experience colic, and don’t cry for long bouts. Research has shown that all babies have an increase in fussiness during the “witching hours,” whether they have colic or not, and this pattern is also seen in hunter-gatherer infants. However, hunter-gatherers engage in practices that have resulted in calmer babies whose needs are immediately met. In the tropical hunter-gatherer groups in existence today, infants are in almost constant skin-to-skin contact. They are worn for most of the day while being exposed to lots of outdoor activities, and most sleep right next to their mother during the night. They also breastfeed frequently, having small frequent feeds on average 4 times an hour. Breastfeeding not only gives them nutrition, but sucking is comforting to them. Additionally, they get a lot of varied stimulation throughout the day, which feeds their rapidly developing brains.

But does that mean that parents of colicky infants aren’t responsive enough or aren’t using the right techniques? Parents of infants who cry a lot will tell you that they have tried everything, and although I have pointed to studies that found a connection with parenting practices in most cases, I have also pointed to one study that found no difference in inconsolable crying when it came to parenting practices. That study included parents who held their baby most of the day and bed shared at night like hunter-gatherers do.

Keep in mind though, if all we are considering and studying is lots of physical contact, we are missing other components of the hunter-gatherer baby experience and how evolutionary biology factors into things. Human infant neuroplasticity is a benefit of being born so highly immature compared to other mammals. The fact that the infantʻs brain has a lot of developing yet to do, allows the brain to be wired in adaptation to the environment the baby is born into. Despite social and motor immaturity, our sense development at birth is more advanced than many other mammals. Human newborns often respond positively to lots of sensory stimulation, needing a rich sensory environment to achieve the wiring that causes their brain to double in size over the first year. Yet culturally we are obsessed with trying to avoid overstimulating them, and we often donʻt understand how developmental stages change the types of stimulation infants desire. Studies that look at how parenting practices might impact colic donʻt get that detailed.

Hereʻs an example of how the right type of stimulation can work in your favor even though your first thought might be to limit stimulation: A couple told me what happened when their 3 month old infant started becoming super distracted at the breast. They said she would pop off early and not complete the feeding. Distraction while nursing is common at that age. One day they discovered that when the mother nursed next to the Christmas tree, the baby would stay on the breast because she was occupied with looking at the lights. Hunter-gatherer babies likely wouldnʻt have feeding issues due to distractions or under stimulation because they eat small, very frequent meals (4 times an hour on average) and are exposed to outdoor sensory environments with lots of movement and interaction with others. Our babies, absent enough sensory stimulation, or the right kind of stimulation for their developmental stage, can become agitated and uncooperative.

The three or four month time period is not only when we tend to see colic disappear, but it also marks the time when infants start to become more social. It is no longer the case that crying is their only source of communication. They are able to smile and vocalize and illicit a response from you by doing so. They can also start bringing toys (or hands) to their mouths and suck on them for comfort or stimulation. The diminishment of colic at this time might just be because the baby starts to have other tools that they can use to get what they want.

Some other reasons that could explain why hunter-gatherers don’t experience colic, go along with many of the colic theories above. They have a more diverse microbiome that is adapted to what they eat and the environment they live in, which is different from the diet and environment found in post-industrial societies. Antibiotic overuse, high c-sections rates, processed foods, environmental pollution, and other factors have had a negative impact on our microbiomes. Hunter-gatherers also don’t consume dairy, so their babies don’t have reactions to cow milk proteins in their mother’s milk. They have less reflux because infants have small, frequent feedings, and they are held (worn) upright most of the day. Hunter-gatherer parents have way more support than we have with 10-20 people at any given time available to help a parent with their baby. Since they are outside a lot and are exposed to sunrise and sunset without artificial lighting, their circadian rhythms are intact and their infants are thus presumably getting enough melatonin in their mother’s milk.

Itʻs possible that there is no one factor that causes colic, or the “witching hours.”

Dr. Harvey Karp is a pediatrician who looked at research done by anthropologists to figure out how to settle crying babies. The problem is, Dr. Karp isnʻt an anthropologist himself, so his Five Sʻs Techniques for calming babies and his Snoo invention, are ideas that were taken out of a hunter-gatherer context and applied in a different social structure and culture in a new way to a less successful effect. Shushing, swaddling, sucking, side-stomach position, and swinging can be helpful at times, but Dr. Karp doesnʻt address cultural differences, what settles infants at various developmental stages, or how evolutionary biology factors into infant needs and responses.

What can you do if your baby is fussy or has colic?

Looking at all of the above data, we can surmise that parenting practices do make a difference in crying in general, with high responsiveness, movement, lots of contact, and the right kind of stimulation most effective for settling babies. However, when it comes to babies who are inconsolable, the issues could possibly be a feeding issue, a food allergy, the microbiome, or a biorhythm problem.

The answer to the question of whether colic in a breastfed infant would improve if they were instead fed formula is an easy no, since colic is present in both breastfed and formula fed infants. There are some other reasons as well. For example, breast milk contains an antibody called IgA that coats the gut and keeps germs and food particles from passing through and getting into the bloodstream. Sometimes food particles pass through the gut anyway, and can cause the body to have an allergic reaction. However, this is far more likely in a formula fed infant since formula does not contain IgA. Also, babies have more reflux with formula than with breast milk.

Formula is cow-milk based, so if your baby has a cow milk protein allergy and you aren’t exclusively nursing, you would need to use hydrolyzed formula. Hydrolyzed formulas work for all but up to 18% of babies with a cow milk protein allergy, so babies who aren't helped by it, have to use amino acid formulas. There are downsides to amino acid formulas. For one, they are 40% more expensive. Additionally, while the impact of amino acid formulas on human babies aren't well studied, the authors of at least one mouse study warn that amino acid formulas may negatively "influence the neuronal development and mental health of [human] children." Soy based formula is an option, but many babies allergic to cow milk proteins are also sensitive to soy, and pediatricians don't recommend soy based formula for infants under 6 months because they have concerns it might negatively impact development.

Many sensitive (or sometimes called gentle) formulas on the market are marketed towards infants who are gassy or fussy. Those formulas remove lactose and replace it with corn syrup. However, lactose is the perfect sugar for infant brain development. Also, the corn syrup formulas come with concerns over their nutritional content, as well as the effects on the infant's metabolism and gut microbiome. One of the theories about why babies get colic is that they have a disrupted gut microbiome, so these formulas potentially could be making colic worse. Furthermore, lactose free formula is suspect because lactose intolerance in infants is extremely rare (human milk is full of lactose so we wouldn't exist if infants couldn't tolerate it).

If you are breastfeeding a baby with an allergy, the assumption in the literature is that an elimination diet is the preferred way to solve the problem. This is in part because of the issues described above with formula, but also, because breast milk has many benefits over formula and the trade off isn't thought to be worth it. This seems dismissive of how hard it is to do an elimination diet, but the gist is that special formula might not solve the original issue or might make the original issue better but cause other issues.

Are you getting enough sunlight in your home?

Exposing your baby to sunlight during the day and limiting artificial light exposure during the night can help them develop their circadian rhythm starting when they are two to three months old. Nursing moms pass circadian hormones on to the baby in their milk, so it could be helpful for you to get enough sunlight in the day and limit blue light (from phones, computers, TVs, LEDs) at night. This will help you sleep as well. It is also helpful to label your milk with the time of day it was pumped so that you can be sure to give the melatonin rich night milk to your baby at night.

To prevent or manage a biorhythm issue, milk that is pumped during the day and night should not be mixed, nor should day milk be given to the baby at night and vice versa. The lactating parent can, as sleep scientists recommend, make sure to be exposed to sunlight during the day and darkness when the sun sets. They recommend limiting exposure to artificial light after sundown, especially from TVs, cellphones, and computers. This ensures that the body sufficiently produces melatonin after sunset, which then gets into the breast milk for the baby in the evening hours. If you live somewhere that isn’t sunny you can try SAD light exposure for 30 minutes upon awakening. That is an easier step than limiting screen time at night.

Melatonin levels in breast milk have been found to be on average 35% of the amount found in the mother’s plasma. Amounts as high as 80% of the parent’s plasma level have been found, however. It is not know at this time if it is helpful for the lactating parent to take melatonin supplements after sunset to increase the amount in the milk. How much of the supplement would get into the milk is unknown but assumed to be low (Hale 2025). However, if there is any benefit to the infant it is only likely if the parent is deficient. The impact of directly giving an infant melatonin is not known and is therefore has not recommended.

While melatonin levels in breast milk have been detected, they have not been detected in cow milk based formula. Therefore, it would not benefit a nursing parent to switch to formula if the baby has colic and low melatonin is a suspected cause.

If your baby has a lot of spit up, make sure the baby isn’t being overfed, and keep them upright for 20 minutes after a feeding. Better yet, wear them throughout the day so that they stay upright. When you change their diaper, roll them to the side instead of lift their legs, and keep their head elevated if you can. When feeding them, keep their head higher than their body. Believe it or not, babies spit up less when lying on their tummy than on their back because of where the esophagus connects to the stomach. You can also lay your infant on their left side. It is safest for babies to sleep on their backs, so these recommendations are for wake time or feeding positions.

A review of studies that looked at whether probiotic supplementation could reduce or end colic determined that probiotics were found to reduce crying time but not stop colic altogether. Supplementation with the L. reuteri stran of bacteria has been recommended. We have a long way to go in our understanding of the microbiome, and might yet discover more effective ways to use prebiotic and probiotic supplements, including the small amounts added to some formula. What is certain is that breast milk contains lots of good bacteria and prebiotic oligosaccharides to give the baby a healthier microbiome. For example, breast milk has about 200 varieties of oligosaccharides while formula with these additives has to date only one variety.

If you have sleep concerns, you might benefit from this podcast on co-sleeping (aka bedsharing or breastsleeping) by an anthropologist who is an infant sleep researcher, or this article addressing what scientists know about sleep training. (Here is the link from further up on sleep myths.)

If you are struggling with crying that is inconsolable, the suggestions for addressing the infant biorhythm and microbiome might be helpful. If things don’t get better, an elimination diet to rule out a food allergy might help. I suggest this last because elimination diets are hard on you. and while some parents notice an immediate difference, it can take up to 4 weeks to fully clear a food out of your system. Also, because it is so hard to do, I definitely recommend seeing a lactation consultant first to rule out any possible feeding issues.

If you are struggling, ask for support from friends, family, a postpartum doula, or nanny. If you are going to hire help, I recommend postpartum doulas over nannyʻs for infants because they usually have specialized training for dealing specifically with infants.

Finally, contact me for help if you live in Chicago! I can help you get to the bottom of whether or not your infantʻs fussiness is related to a feeding or sleep issue, or is related to developmental changes. Often, these things are all connected. I can also help you with what types of stimulation your baby needs based on their developmental needs. Before you go through the trouble of trying out various remedies or elimination diets, which can be expensive, extremely time consuming, and stressful, it can be helpful to have an expert identify or eliminate issues.